Terfezia and Tirmania, Desert

Truffles (terfez, kama, p/faqa)

Terfezia and Tirmania, Desert

Truffles (terfez, kama, p/faqa)Delicacies in the sand or manna from Heaven?

Terfezia and Tirmania, Desert

Truffles (terfez, kama, p/faqa)

Terfezia and Tirmania, Desert

Truffles (terfez, kama, p/faqa)

Delicacies in the sand or manna from Heaven?

Tom Volk's Fungus of the Month for January 2007

by Elinoar Shavit and Tom Volk Please click

TomVolkFungi.net for the rest of Tom Volk's pages on fungi

Welcome to the tenth anniversary edition of the Fungus of the Month! Since the first Fungus of the Month in January 1997 was a truffle (Tuber gibbosum, the Oregon white truffle), I decided on another truffle for this month's fungus. My good friend Elinoar Shavit, an Israeli native, has written most of this web page on the desert truffle, found in the Middle East and along the southern Mediterranean coast. I hope you will enjoy this tenth anniversary page and continue to enjoy ten years of Fungus of the Month pages. Thanks for visiting!

Truffles are hypogeous fungi, which means they form their fruitbodies

below ground. Ecologically, they are mycorrhizal, forming mutually beneficial associations

with the roots of plants. Taxonomically, they are members of the Ascomycota (having a saclike

ascus that contains the ascospores). Like most other hypogeous fungi, desert truffles depend on animals to disperse their spores. Toward this end, the ripening fruitbodies omit a distinct aroma, which grows stronger as they mature. The aroma attracts a variety of animals (humans included) who eagerly collect and consume the truffles, and later disperse the spores to new areas, usually in their feces.

The most common species of the genus Terfezia are Terfezia

arenaria

(syn. T. leonis),

T. boudieri, T.

claveryi, T. leptoderma, and T.

terfezioides (=Mattirolomyces

terfezioides) and although just separated

- T. pfeilii

(syn. Kalaharituber

pfeilii). The most common species of

the genus Tirmania

are Tirmania nivea and

T. pinoyi (syn. T.

africana).

Terfezia spp.

have spherical and ornamented spores, while Tirmania

spp.

have smooth spores and amyloid asci. The fruitbodies are round, tan to

brown, and look like small, sandy potatoes. They are a few centimeters

across, and weigh about 1-10 oz. The truffles produced by both genera

are similar in overall look, and are not easy to tell apart. A simple

iodine test can separate them. A drop of iodine on the cut flesh of

Terfezia

fruitbody will not change or turn yellow to orange. Cut

fruitbodies of Tirmania

will turn blue-green to black. The color of

their gleba (the flesh of the fruitbodies) depends on the species, and

its shade can be white to light cream, cream to yellow, and even pink.

At this stage the spores are unripe, and they will ripen once the

truffle matures, usually above the ground in the sun. The gleba is then

much darker and can even be black. Their unique flavor develops as they

reach maturity. There is a close genetic relationship between species of

Tirmania

and

Terfezia,

and they may have arisen from a single evolutionary lineage

of fungi that adapted to the heat and drought by growing its

fruitbodies underground. Terfezia

spp. generally prefer semi-arid

habitats, and Tirmania

spp. are more adapted to arid deserts, but

species of both genera often share the same habitat, and even the same

Helianthemum

host, forming their fruitbodies around it. This may show

that the initiation of a fruitbody by one species is not inhibited by

the initiation of another fruitbody close by. The truffles of both

genera grow at the end of the rainy season, in spring, usually between

March and June.

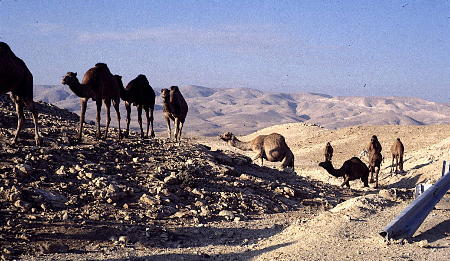

‘Desert truffle’ is a term used to refer to members of the genera

Terfezia and Tirmania in the family Terfeziaceae, order Pezizales, which grow in arid and semi-arid areas of the Mediterranean region, the Arabian Peninsula, and North-Africa. Some have been found in South Africa and China. The photograph to the right was taken by Dr. Nissan Binyamini in the Israeli Negev Desert. Nissan Binyamini wrote the only mushroom guide for amateurs in Hebrew, and headed the Dept. of Botany at the Tel Aviv University for many years. Species of Terfezia and Tirmania prefer high pH calcareous soils, typical of desert soils. Although the genera Terfezia and Tirmania are primarily ectomycorrhizal (forming a sheath around the roots of their host plant), they are highly adaptable. Some species, like Terfezia arenaria, Terfezia claveryi, and Tirmania pinoyi, form endomycorrhizal associations in phosphate-poor soils and ectomycorrhizal associations in phosphate-rich soils. Species of both genera form mycorrhizas on roots mainly of members of the genus Helianthemum (family Cistaceae), relatives of the North American rock rose, but can also form relationships with members of other families in the absence of species of Helianthemum. These relationships contribute to Helianthemum’s adaptability to drought conditions and facilitate absorption of nutrients, particularly nitrates. This finding

may provide an explanation for folklore shared by Bedouins in the Israeli Negev and truffle hunters in Morocco, claiming that truffles

will grow where lightning strikes during thunderstorms. ( more on this subject)

‘Desert truffle’ is a term used to refer to members of the genera

Terfezia and Tirmania in the family Terfeziaceae, order Pezizales, which grow in arid and semi-arid areas of the Mediterranean region, the Arabian Peninsula, and North-Africa. Some have been found in South Africa and China. The photograph to the right was taken by Dr. Nissan Binyamini in the Israeli Negev Desert. Nissan Binyamini wrote the only mushroom guide for amateurs in Hebrew, and headed the Dept. of Botany at the Tel Aviv University for many years. Species of Terfezia and Tirmania prefer high pH calcareous soils, typical of desert soils. Although the genera Terfezia and Tirmania are primarily ectomycorrhizal (forming a sheath around the roots of their host plant), they are highly adaptable. Some species, like Terfezia arenaria, Terfezia claveryi, and Tirmania pinoyi, form endomycorrhizal associations in phosphate-poor soils and ectomycorrhizal associations in phosphate-rich soils. Species of both genera form mycorrhizas on roots mainly of members of the genus Helianthemum (family Cistaceae), relatives of the North American rock rose, but can also form relationships with members of other families in the absence of species of Helianthemum. These relationships contribute to Helianthemum’s adaptability to drought conditions and facilitate absorption of nutrients, particularly nitrates. This finding

may provide an explanation for folklore shared by Bedouins in the Israeli Negev and truffle hunters in Morocco, claiming that truffles

will grow where lightning strikes during thunderstorms. ( more on this subject)

It has been shown that plenty of rain in the beginning of the rainy season is necessary to ensure a good truffle crop in spring. Even so,

many truffle hunters, including the Bedouins of the Negev, believe that truffles appear suddenly, without seed or root, swollen by early

season’s rains, and loosened from their sandy bed by the loud rumblings of strong thunderstorms. These beliefs go back thousands of years. In 1st century C.E., Pliny the Elder (Gaius Plinius Secundus), wrote in his Naturalis

Historia, Book xix, “Among

the most

wonderful of all things is the fact that anything can spring up and

live without a root. These are called truffles (tubera). They are

surrounded on all sides by earth, and supported by no fibers. There are

two kinds: one is sandy and injures the teeth, the other without any

foreign matter. Those of Africa are the most esteemed. Peculiar beliefs

are held for they say that they are produced during autumn rains, and

thunderstorms especially, and are best for food in the spring. They

grow…where there is much sand.” The

Jewish Talmud (the record of rabbinic discussion of the Jewish law), echoed the same

claim. Truffles and mushrooms are usually discussed together in the

Babylonian Talmud (compiled and redacted in Iraq in the 5th Century

C.E.). The Rabbis considering the issue concluded that truffles and

mushrooms do not grow from the soil. Rather, they spontaneously appear

in the soil. In one place it is said that, “they

emerge as they are in one night, wide and round like rounded cakes”.

It has been shown that plenty of rain in the beginning of the rainy season is necessary to ensure a good truffle crop in spring. Even so,

many truffle hunters, including the Bedouins of the Negev, believe that truffles appear suddenly, without seed or root, swollen by early

season’s rains, and loosened from their sandy bed by the loud rumblings of strong thunderstorms. These beliefs go back thousands of years. In 1st century C.E., Pliny the Elder (Gaius Plinius Secundus), wrote in his Naturalis

Historia, Book xix, “Among

the most

wonderful of all things is the fact that anything can spring up and

live without a root. These are called truffles (tubera). They are

surrounded on all sides by earth, and supported by no fibers. There are

two kinds: one is sandy and injures the teeth, the other without any

foreign matter. Those of Africa are the most esteemed. Peculiar beliefs

are held for they say that they are produced during autumn rains, and

thunderstorms especially, and are best for food in the spring. They

grow…where there is much sand.” The

Jewish Talmud (the record of rabbinic discussion of the Jewish law), echoed the same

claim. Truffles and mushrooms are usually discussed together in the

Babylonian Talmud (compiled and redacted in Iraq in the 5th Century

C.E.). The Rabbis considering the issue concluded that truffles and

mushrooms do not grow from the soil. Rather, they spontaneously appear

in the soil. In one place it is said that, “they

emerge as they are in one night, wide and round like rounded cakes”.

Desert truffles are called by a number of different names and

by variations of these names. They are called terfez or terfas in Morocco, Libya, and Egypt. Since truffles were shipped from North Africa to the Roman Empire for many years, terfez

may be the source of the scientific name for the genus Terfezia. The white Tirmania nivea

is called zubaydiya in Saudi Arabia and Oman, and the Nama people of Namibia call the Kalahari truffle: “! / nabba” (the “!” stands for a click of the tongue on the upper palate, combined with an ‘N’ sound). However, the most prevalent names by which desert truffles are called all over the Arabian peninsula and the Eastern shores of the Mediterranean, are variations on the words kama and faqa. These are ancient

terms which

have been used in the region for thousands of years, and still refer to

truffles in modern Arabic, Hebrew, and Aramaic. The term

‘pagua’

is even mentioned in the Bible.

Desert truffles are called by a number of different names and

by variations of these names. They are called terfez or terfas in Morocco, Libya, and Egypt. Since truffles were shipped from North Africa to the Roman Empire for many years, terfez

may be the source of the scientific name for the genus Terfezia. The white Tirmania nivea

is called zubaydiya in Saudi Arabia and Oman, and the Nama people of Namibia call the Kalahari truffle: “! / nabba” (the “!” stands for a click of the tongue on the upper palate, combined with an ‘N’ sound). However, the most prevalent names by which desert truffles are called all over the Arabian peninsula and the Eastern shores of the Mediterranean, are variations on the words kama and faqa. These are ancient

terms which

have been used in the region for thousands of years, and still refer to

truffles in modern Arabic, Hebrew, and Aramaic. The term

‘pagua’

is even mentioned in the Bible.

Even though they are formed underground, the fruitbodies of desert truffles are not very deep and can be visible to the trained eye. They are connected to their rhizomorphs and to their host’s roots by a stalk-like formation made of hyphae. It is thin, but some species form a thick ‘stem’ that can reach a length of 40cm. Local truffle hunters believe that this stem pushes the truffle out of the ground. In his book, “The Bedouins and the Desert”, Jibrail Jabbur writes, “If left ungathered, the white truffle [Tirmania nivea] grows underground by leaps and bounds until it bursts through and appears on the surface of the ground. When it has reached its maximum size, it sometimes rolls out of the mouth of its little ‘volcano’ and its skin begins to wrinkle…in the sun”. Exposed ripe desert truffles spoil within a few hours, and are often overtaken by insect larvae. Truffle collectors hunt for them in the early hours of the morning. The sun light reflecting off of the dew drops on the sand particles helps detect the cracked bumps in the sand, which are the tell tale signs of a truffle emerging. Because desert truffles grow so close to the surface, there is no need to use pigs or trained dogs to find them. Experienced truffle collectors can detect an emerging truffle from a distance, and often return season after season to the same areas, keeping the locations of their favorite spots a secret.

Where desert truffles grow, people eagerly await their appearance. They are collected for their unique flavor, nutritional value, and medicinal properties. For these reasons, they have always been in demand, making them a lucrative cash crop for local populations. In the past few years, the demand for desert truffles in Europe has been growing rapidly. It occupies a special niche, and benefits from the growing Middle Eastern population in Europe and from the Europeans’ traditional passion for truffles. Terfez from North Africa reach the European markets each spring, and even the Kalahari truffle has a market in Germany. Irrigation of the native truffle producing areas in times of drought could help secure a more predictable supply of truffles to the growing markets. Efforts have been made to cultivate desert truffles in Turkey, Israel, Saudi-Arabia, Namibia and other places within their growing areas, but so far with only modest success.

Truffles have always been a popular delicacy. Kamma were craved by rulers of Mesopotamia. In the excavations of the 4000 year old Amorite palace in Tel-Hariri (eastern Syria), archeologists found remnants of truffles still in their special baskets as well as mentions of them in the palace’s inventory lists. The Pharaohs of ancient Egypt cherished them as food… fit for the Pharaohs, and arranged for large quantities to be brought to their palaces. The Roman Emperors regularly imported massive quantities of terfez from Libya and Greece. In the Jewish Mishna (first recording of the Jewish oral law, redacted around the 2nd Century C.E.), truffles (‘kmehin’ in plural) symbolize plenitude and Devine reward, as presented by the 1st Century B.C.E. story of Honi the Circle Drawer.

The Bedouins have always held truffles in high esteem, and

consider

them a special gift. Their folklore includes stories about the

contribution of truffles to Bedouin life. In his travels across the

deserts of Arabia, Jibrail Jabbur observed Bedouins collecting their

most appreciated truffle, the White Truffle, Terfezia nivea. In

“Bedouins and the Desert” he writes, “its

skin and pith are both white, its pith is softer, neither as firm nor

as round as the brown and black truffle. The Bedouin calls them Shaykh

[the leader of a Bedouin tribe] and when the Bedouin girl is collecting

truffles she sings to them…I personally saw a white

Shaykh… and dug it out with my own hands. It weighed more

than 1,400 grams [about 3 lbs] and measured 24 cm [about 10 inches] in

diameter. From a distance I thought it was a large rock, since it lay

exposed on the surface of the ground, as white truffles generally do

when they are fully mature”.

The Bedouins have always held truffles in high esteem, and

consider

them a special gift. Their folklore includes stories about the

contribution of truffles to Bedouin life. In his travels across the

deserts of Arabia, Jibrail Jabbur observed Bedouins collecting their

most appreciated truffle, the White Truffle, Terfezia nivea. In

“Bedouins and the Desert” he writes, “its

skin and pith are both white, its pith is softer, neither as firm nor

as round as the brown and black truffle. The Bedouin calls them Shaykh

[the leader of a Bedouin tribe] and when the Bedouin girl is collecting

truffles she sings to them…I personally saw a white

Shaykh… and dug it out with my own hands. It weighed more

than 1,400 grams [about 3 lbs] and measured 24 cm [about 10 inches] in

diameter. From a distance I thought it was a large rock, since it lay

exposed on the surface of the ground, as white truffles generally do

when they are fully mature”.

The Bedouins of the Negev use truffles for food, as a cash crop and as medicine for a variety of ailments. They dry them and use the flour for stomach ailments, and open cuts. They use the juice of the truffles to treat eye infections. They were recommended by the Prophet Muhammad (in the 7th Century C. E.), especially for problems of the eyes. It is written in the Tirmidhi Hadith (No. 1127), “When some companions of Allah’s Messenger (peace be upon him) remarked to him that truffles were the smallpox of the earth, he replied, “Truffles are a kind of Manna, which Allah the Glorious and Exalted sent down upon the people of Israel, and their juice is a remedy for the eyes”. The Bedouins in the Negev do not allow truffles anywhere near fermenting milk when preparing samene (fermented butter, similar to gee). They say that it will stop the delicate process of fermentation. Antibacterial substances have been isolated from the juice of a variety of desert truffles. In 2004, a Jordanian research team isolated a promising peptide antibiotic from the juice of Terfezia claveryi, which effectively inhibited the growth (in vitro) of Staphylococcus aureus by 66.4%.

Desert truffles are nutritious, and particularly high in protein. In good seasons, truffles are dried and ground to powder to supplement the regular diet. Even though the unique aroma of the truffles cannot be preserved by drying, the nutritious flour is added to a mixture of flatbread, which is then baked and eaten with honey. In times of famine, people have been known to rely on truffles. Particularly compelling is the story of an Iraqi woman who describes bad times during the 1970’s in Baghdad, when her family and neighbors could not get food for months. According to the Iraqi woman, one year truffles were so plentiful that people prepared them in the same way they would normally prepare meat. They ate desert truffles every day for four months, cooking them in every imaginable manner. Yet at the end of this period, she had not tired of them, still finding them nutritious and tasty.

Traditionally, desert truffles are cooked simply, so as not to

mask

their delicate aroma. The oldest way, which is still very popular

today, is to roast them in the embers of the fire. Truffles are also

baked, sliced and fried in butter. They are made into fragrant soups,

usually with camel’s milk. A very popular dish, served at

souks and restaurants all over the Middle East, is scrambled eggs with

desert truffles, served in a pita-pocket. (recipes

with desert truffles)

Traditionally, desert truffles are cooked simply, so as not to

mask

their delicate aroma. The oldest way, which is still very popular

today, is to roast them in the embers of the fire. Truffles are also

baked, sliced and fried in butter. They are made into fragrant soups,

usually with camel’s milk. A very popular dish, served at

souks and restaurants all over the Middle East, is scrambled eggs with

desert truffles, served in a pita-pocket. (recipes

with desert truffles)

In a few months, the time will be right to travel to Morocco, Israel, Turkey or Namibia, to collect desert truffles. But before you pack your bag, consider this: Truffle hunters in Namibia carry a special ‘snake stick’ to ward off poisonous adders when they go truffle hunting. Poisonous snakes have always been a problem probably because both truffles and snakes prefer the damper areas in the shade of the plants. A famous Rabbi who lived in Iraq in the 4th century C.E., warned consumers to stay away from truffles that have holes (probably caused by insect larvae). The reason he gave: those holes could be the teeth marks of venomous snakes!

This month's co-author is Elinoar Shavit, a renowned gemologist by trade. She was born in Israel and now lives near Boston. She has an M.A. in Organizational Psychology from Columbia University, and she is a past President of the New York Mycological Society. She has been collecting mushrooms practically from birth, first with her grandmother, then with her mother, and now with her family and friends. In the past few years she has been traveling in the US and abroad, following the growing seasons of morels, truffles and other edible mushrooms, to collect the stories of mushroom hunters, which she intends to publish in a book. You can email her at

This month's co-author is Elinoar Shavit, a renowned gemologist by trade. She was born in Israel and now lives near Boston. She has an M.A. in Organizational Psychology from Columbia University, and she is a past President of the New York Mycological Society. She has been collecting mushrooms practically from birth, first with her grandmother, then with her mother, and now with her family and friends. In the past few years she has been traveling in the US and abroad, following the growing seasons of morels, truffles and other edible mushrooms, to collect the stories of mushroom hunters, which she intends to publish in a book. You can email her at

I hope you enjoyed learning about Terfezia and Tirmaina, the desert truffles. There's always something fun to find if you visit another part of the world. I hope to visit some day to taste these fungi. All we get here are chocolate "dessert truffles" instead of the more delicious "desert truffles."

Learn more about fungi! Go to Tom Volk's Fungi Home Page --TomVolkFungi.net

Return to Tom Volk's Fungus of the month pages listing

Bibliography