This month's fungus is the beautiful blue-green cup-fungus Chlorociboria aeruginascens and its close relative, Chlorociboria aeruginosa.

It's actually a very common fungus, although it is more common to see the green stained wood than to actually see the fruiting bodies.

They are Ascomycetes belonging to the family Helotiaceae of the order Helotiales, which includes other cup fungi such as the yellow Bisporella citrina and the purple Ascocoryne sarcoides. The order Helotiales has inoperculate asci-- this means that their asci (which bear the ascospores) do not open by a hinged lid called an operculum. The operculate cup fungi in the order Pezizales are much more well known and include morels, black tulip fungi, and various kinds of faerie cups, such as Microstoma floccosum, Aleuria aurantia, Sarcoscypha occidentalis, and Geopyxis carbonaria.

The two species of Chlorociboria are very similar to each other macroscopically and only differ microscopically by the size of their ascospores. The spores of Chlorociboria aeruginosa are typically larger (9-14 x 2-4 Ám) than those of C. aeruginascens (5-7 x 1-2 Ám). These two fungi are distributed throughout the temperate forests of the world and are the only two species of Chlorociboria found in North America. New Zealand has 15 different species, some of which like highly rotten wood while others prefer harder wood.

In the case of Chlorociboria, the cups can be stalked or unstalked, are 0.2 - 0.6 cm in diameter, and are a stunning blue-green against the forest floor. Most of the time you don't see the actual fruiting bodies but the brilliantly green-stained wood of hardwoods, including poplar, aspen, oak and ash. Woodworkers call this wood "green rot" or "green stain." Chlorociboria species are not considered "true" wood decay fungi as are the white-rot and brown-rot Basidiomycetes [click here for more explanation about how basidiomycetes decay lignin and cellulose], but these ascomycetes may be soft-rot fungi that can cause small amounts of erosion in the wood cell walls. It is also possible that they do not degrade the cell wall directly but colonize wood decayed by other fungi earlier in the decay process.

In the case of Chlorociboria, the cups can be stalked or unstalked, are 0.2 - 0.6 cm in diameter, and are a stunning blue-green against the forest floor. Most of the time you don't see the actual fruiting bodies but the brilliantly green-stained wood of hardwoods, including poplar, aspen, oak and ash. Woodworkers call this wood "green rot" or "green stain." Chlorociboria species are not considered "true" wood decay fungi as are the white-rot and brown-rot Basidiomycetes [click here for more explanation about how basidiomycetes decay lignin and cellulose], but these ascomycetes may be soft-rot fungi that can cause small amounts of erosion in the wood cell walls. It is also possible that they do not degrade the cell wall directly but colonize wood decayed by other fungi earlier in the decay process.

The discoloration is caused by the production of the pigment xylindein, which is classified by chemists as a napthaquinone. This pigment exists in several different forms of different color within the wood cells; the combination of a yellow-orange form with a blue-green form results in the dazzling blue-green coloration of the colonized wood. Xylindein can inhibit plant germination and has been tested as an algaecide. It may make wood less appealing to termites, and has been studied for its cancer-fighting properties.

The discoloration is caused by the production of the pigment xylindein, which is classified by chemists as a napthaquinone. This pigment exists in several different forms of different color within the wood cells; the combination of a yellow-orange form with a blue-green form results in the dazzling blue-green coloration of the colonized wood. Xylindein can inhibit plant germination and has been tested as an algaecide. It may make wood less appealing to termites, and has been studied for its cancer-fighting properties.

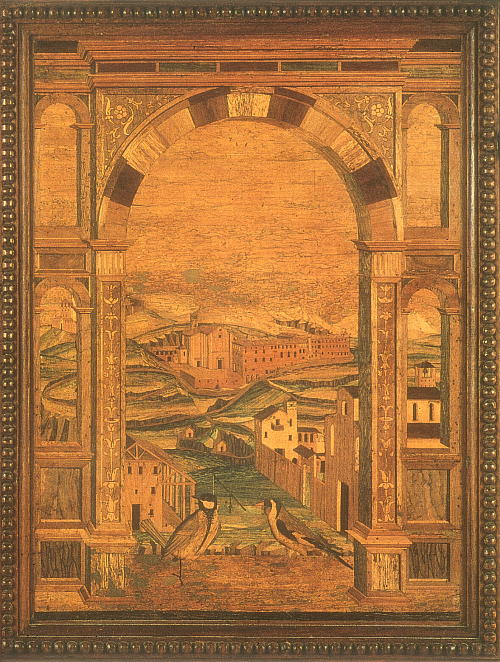

Woodworkers have prized Chlorociboria-stained wood for centuries. Dr. Robert Blanchette at the University of Minnesota showed that 14th and 15th century Renaissance Italian craftsmen used the wood to provide the green colors in their intricate inlaid intarsia designs. Using electron microscopy, he was able to show that green-colored wooden splinters taken from the Italian artwork were identical to Chlorociboria-colonized wood obtained in modern northern Minnesota. In the 18th century, English woodworkers in the town of Tunbridge Wells, Kent, started using small splinters and veneers of the green-stained wood to form highly detailed pictures of animals, flowers, local landscapes, and geometric designs, which were often inset into the lids of small wooden boxes. These antiques are called "Tunbridge ware" and are very valuable today. Click here for more of these beautiful inlaid wood pictures.

Woodworkers have prized Chlorociboria-stained wood for centuries. Dr. Robert Blanchette at the University of Minnesota showed that 14th and 15th century Renaissance Italian craftsmen used the wood to provide the green colors in their intricate inlaid intarsia designs. Using electron microscopy, he was able to show that green-colored wooden splinters taken from the Italian artwork were identical to Chlorociboria-colonized wood obtained in modern northern Minnesota. In the 18th century, English woodworkers in the town of Tunbridge Wells, Kent, started using small splinters and veneers of the green-stained wood to form highly detailed pictures of animals, flowers, local landscapes, and geometric designs, which were often inset into the lids of small wooden boxes. These antiques are called "Tunbridge ware" and are very valuable today. Click here for more of these beautiful inlaid wood pictures.

The growth conditions for wood colonization are largely unknown and are being studied by scientists at the Center for Forest Mycology Research in the Northern Research Station and the Forest Products Laboratory of the U.S. Forest Service in Madison, WI. The goal of this research is to develop ways to inoculate wood with stain and spalting fungi in order to create "value added" materials from low value wood species for the woodworking industry.

We hope that you enjoyed learning about these little green-stain fungi. They're fun to find in the woods. It's even fun to find the green stained wood without seeing the fruiting bodies. You can read more about them and the use of their pigmented wood in the following articles:

Blanchette, R.A., Wilmering, A.M., and Baumeister, M. 1992. The use of green-stained wood caused by the fungus Chlorociboria in intarsia masterpieces from the 15th century. Holzforschung 46: 225-232.

Kuo, M. (2004, November). Chlorociboria aeruginascens & C. aeruginosa. Retrieved from the MushroomExpert.Com Web site: http://www.mushroomexpert.com/chlorociboria_aeruginascens.html

This month's co-author is Jessie Micales Glaeser, who works at the Center for Forest Mycology Research, which is a part of the USDA Forest Service in Madison, Wisconsin, where I worked from 1989-1996. She is interested in wood decay and wood-stain fungi and is also a competitive fencer!

This month's co-author is Jessie Micales Glaeser, who works at the Center for Forest Mycology Research, which is a part of the USDA Forest Service in Madison, Wisconsin, where I worked from 1989-1996. She is interested in wood decay and wood-stain fungi and is also a competitive fencer!

If you have anything to add, or if you have corrections, comments, or recommendations for future FotM's (or maybe you'd like to be co-author of a FotM?), please write to me at

This page and other pages are © Copyright 2008 by Thomas J.

Volk, University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.

Learn more about fungi! Go to Tom Volk's Fungi Home Page --TomVolkFungi.net

Return to Tom Volk's Fungus of the month pages listing

More pictures of inlaid wood from Bob Blanchette.

All of the green is wood stained by Chlorociboria