Please click

TomVolkFungi.net for the rest of Tom Volk's pages on fungi

This month's fungus is one of my favorite little mushrooms to find in the woods. It's rather common, especially on old rotted stumps. Most importantly, when you find one, you will always see several hundred more on the same stump! When you find Xeromphalina kauffmanii, you can significantly increase the "mushroom count" for your foray (although it doesn't do much for those who count weight instead of number...).

This month's fungus is one of my favorite little mushrooms to find in the woods. It's rather common, especially on old rotted stumps. Most importantly, when you find one, you will always see several hundred more on the same stump! When you find Xeromphalina kauffmanii, you can significantly increase the "mushroom count" for your foray (although it doesn't do much for those who count weight instead of number...).

When I see so many of these mushrooms on one stump, I suspect they are mostly from the same mycelium, from the same individual. I guess I have no reason to assume this, but they all look identical, and they all come out at the same time on any given log. Let's assume for now they all come from the same individual. Why would a mycelium produce many mushrooms rather than just a few larger ones? I don't really have an answer to that question, but I would speculate that the mycelium is hedging its bets by putting its "eggs" (spores) in many "baskets," rather than making one or a few large fruiting bodies with many spores, as do giant puffballs, matsutake, and many others. Anyone else have any ideas about this basket hypothesis?

However, the entire premise for this argument may be wrong-- the fruiting bodies may be from many different individuals. For example, when you see a log filled with turkey tails, most often there are several individuals competing with one another for the limited amount of food in the log. You can see evidence of this competition by cutting the log below the fruiting bodies and seeing the black zone lines that indicate competition between individuals as they try to fight each other off. You may know this as spalted wood. In any case, different fungal species certainly have different strategies for reproduction.

The genus Xeromphalina is relatively easy to distinguish from other genera of gilled mushrooms because of the abundant cross-veins that connect the gills with one another, as shown in the picture to the right. In addition the fruiting bodies are rather rubbery to cartilaginous, especially the stems. Usually the stem is a darker color than the gills.

The genus Xeromphalina is relatively easy to distinguish from other genera of gilled mushrooms because of the abundant cross-veins that connect the gills with one another, as shown in the picture to the right. In addition the fruiting bodies are rather rubbery to cartilaginous, especially the stems. Usually the stem is a darker color than the gills.

There are actually two common species of cross-veined troop mushrooms that are very similar to one another: Xeromphalina kauffmanii and X. campanella. Both species are about the same color and size and shape. The easiest way to distinguish between them is by identifying the substrate. Xeromphalina kauffmanii grows on hardwood trees (angiosperms), while X. campanella grows on conifers (gymnosperms). Ron Peterson and others, of the University of Tennessee, have done mating studies with these two species, and so far the hardwood/conifer distinction is holding up. Mating studies determine what we call a "Biological Species." Any two individuals that can mate with one another and form fertile offspring are considered to be the same Biological Species. This does not specifically consider whether mating actually takes place in nature-- this would be very hard to test. However, with fungi that can be cultured in Petri dishes in the lab, the mating tests are relatively easy to do-- although not always easy to read.

There are three main species concepts that are used in identifying fungi. I'll just give you a brief description of the three most important ones here, and someday I'll write a whole webpage about species. I've already given a lecture on "What is a species?" to various mycological clubs.

- Morphological Species. This involves the analysis of traditional morphological characters, including macroscopic and microscopic characters of the fruiting bodies. The analysis often requires years (often a lifetime) of studies of dozens of fruiting bodies of closely related species. There is really quite a bit of "art" to this species concept.

- Evolutionary Species. Any two individuals that can be traced to a common ancestral lineage are considered to be the same species. This concept is almost entirely based on analysis of DNA, RNA, lipids, and proteins.

- Biological Species . Populations of fungi that are compatible (i.e. that can mate) with one another are considered to be of the same biological species. This analysis is limited to those fungi that can be cultured. Thus obligate mutualists (like most mycorrhizae that are dependent on the host plant for survival) and obligate pathogens (which must grow on a living host) cannot easily be tested using this concept.

In any case, there does not appear to be any mating between the Xeromphalina that grows on hardwoods with the Xeromphalina that grows on conifers, so we must consider them to be the same Biological Species.

There is one other Xeromphalina that I think is really pretty, namely X. tenuipes. At first glance it does not look like the other Xeromphalina species. Although it's hard to tell from this picture, it's more than 10X larger than the other species and usually found singly or in groups of up to ten fruiting bodies. However, if you look at the gills of this species you can see that they are cross-veined as well. I'm not sure what it is I like about this mushroom. I think it must be something about the colors, especially the contrast between the stem and the gills and the gradation of colors.

There is one other Xeromphalina that I think is really pretty, namely X. tenuipes. At first glance it does not look like the other Xeromphalina species. Although it's hard to tell from this picture, it's more than 10X larger than the other species and usually found singly or in groups of up to ten fruiting bodies. However, if you look at the gills of this species you can see that they are cross-veined as well. I'm not sure what it is I like about this mushroom. I think it must be something about the colors, especially the contrast between the stem and the gills and the gradation of colors.

So far as we know Xeromphalina kauffmanii and its relatives are not edible, but not poisonous either. Each individual mushroom is so small that it would be hard to collect enough to make a meal anyway. Plus they are so tough and rubbery that you'd have to spend half an hour chewing each bite. Add to this the fact that they have no significant flavor, and this is not a mushroom you'd want to pick for the table. However, it is not known to be poisonous either. I would doubt that anyone has eaten enough of them to accurately test their toxicity. Any experimenters out there?

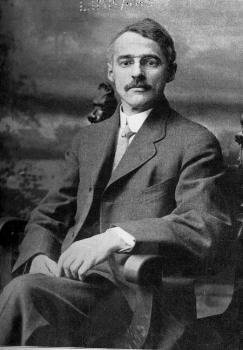

This month's fungus is named in honor of Calvin Henry Kauffman, who was a professor of Mycology at the University of Michigan from 1904-1931. He was really the first mycologist to call attention to and extensively study midwestern mushrooms. He published "The Agaricaceae of Michigan" in 1918, a 2-volume very extensive reference with pictures and excellent dichotomous keys to the mushrooms. Although

This month's fungus is named in honor of Calvin Henry Kauffman, who was a professor of Mycology at the University of Michigan from 1904-1931. He was really the first mycologist to call attention to and extensively study midwestern mushrooms. He published "The Agaricaceae of Michigan" in 1918, a 2-volume very extensive reference with pictures and excellent dichotomous keys to the mushrooms. Although some many of the names have changed, Kauffman's keys still work very well for keying out most midwestern mushrooms. You might be able to find this book as a 1971 Dover publishers reprint retitled "The Gilled Mushrooms (Agaricaceae) of Michigan and the Great Lakes Region." Notice that "Kauffman" has two "f's" and one "m" in his name. I always have trouble remembering. The Latinized version of his name is "kauffmanius," so the epithet, meaning "of kauffman," has to be "kauffmanii" with two "i's" at the end. That's why Latin is a dead language.

The genus name Xeromphalina also has an interesting origin. "Xero" means dry, while "omphal" means navel or belly button, and "-ina" is a suffix added to denote a small size. Thus Xeromphalina means "small dry belly button." I will let you use your imagination as to why this is a very appropriate name. I think it's important to know what the Latin names mean, especially descriptive ones like this that help you remember them.

I hope you enjoyed learning about the cross-veined troop mushroom Xeromphalina kauffmanii and its relatives. It's fun to find these bright yellow-orange mushrooms in the woods, making a very pretty contrast with the dark, rotten logs. Good luck on your hunting!

If you have anything to add, or if you have corrections, comments, or recommendations for future FotM's (or maybe you'd like to be co-author of a FotM?), please write to me at

This page and other pages are © Copyright 2006 by Thomas J.

Volk, University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.

Learn more about fungi! Go to Tom Volk's Fungi Home Page --TomVolkFungi.net

Return to Tom Volk's Fungus of the month pages listing